An Interpretation of the Mastiff Breed Standard

by Betty Baxter & David Blaxter (Illustrated)

This recreation of the illustrated interpretation of the mastiff breed standard has been greatfully granted by kind permission of both Betty Baxter and David Blaxter. Co-authors of their much loved book "The Complete Mastiff".

Anybody interested in the breed is bound to ask: How have we got the Mastiff that we see today? What has gone into the making of our dogs? Have they reached the final stage of their development, or will we try to alter them to suit our own requirements?

Although Mastiffs were originally Dogs of War and Baiting dogs, they have always been primarily guards of people and property. The description by Conrad Heresbatch, published in 1586 in the Foure Bookes of Husbandrei, is still relevant today: "His disposition must be neither too gentle nor too crust, neither fawn upon a thief or fly for his friends". These dogs were almost certainly not as huge as today's Mastiffs; they were probably lighter and quicker, and certainly fiercer, but similar in many respects. Throughout the ages, dogs were kept and bred for what they could do, and not necessarily for what they looked like - that change occurred with the formation of the Kennel Club and the start of exhibiting dogs in shows.

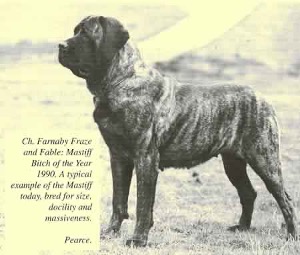

We have made our Mastiffs bigger, heavier, stronger, perhaps less mobile, and certainly milder in temperament. How closely the type resuscitated by enthusiasts in the 1800's resembled their forebears in all points, it would be hard to say. Our present Mastiffs in some ways resemble those that were being produced at the beginning of the 19th century, although they are unlike in other ways. For example, with the introduction of St Bernard or Alpine blood, bone became denser and heads broader and wider, and muzzles deeper. All changes have come about gradually over the years and not, of course, overnight. Attitudes have also changed towards dog keeping, and today's Mastiff is the result of years of careful breeding.We have a breed, which, despite the outcrosses which have proven necessary upon occasions, is a very ancient and very honourable one. We have bred for size, docility, and massiveness, while still trying to retain the admirable characteristics which have made the Mastiff, throughout the ages, a superb guard and companion. The finished product certainly resembles pictures of Mastiffs of one hundred years age - and even those of two hundred years age, in most respects, while differing in others. We must always remember that we have an enormous responsibility towards this wonderful breed, and hopefully, where changes have taken place, they have been for the better.

It must be said that after the Second World War, the dire shortage of breeding stock and the resulting massive in-breeding meant that the soundness in the breed was very bad. If a dog had a pleasing head and looked good while standing, then it would win, even with appalling movement. Today this attitude is, thankfully, a thing of the past, and movement is generally sound. After all, it is no use having a wonderful looking dog who is a cripple, but conversely it is no use having a dog that can move like a dream who looks like a Great Dane and has no breed type.

It is certainly difficult to get everything that is required: breed type, soundness and good temperament, but these are the criteria that today's breeders must bear in mind. Despite the changes which we have made, we have kept the original type of dog, and we can look back through many hundreds of years of history and realise that our Mastiff of today does go back to the 'dogs of the Ancient Britons'. And what we have now, we should try to keep. We do not need more changes, and we now have enough breeding stock to make outcrosses unnecessary. Today's Mastiff is the amalgam of all that has gone before, and as such is something to be greatly valued.

Drawing Up The Breed Standard

It is obvious that a Breed Standard is no less that the actual blueprint of the breed. The English Mastiff Breed Standard was drawn up in the very early days of the Old English Mastiff Club, in the last century, and has remained virtually unaltered ever since. This particular Standard is one of the very few that makes no mention of height or weight. Most Standards in other countries, especially those that are members of the FCI, are based on the English Standard (as the breed's country of origin), which is then translated into the native tongue. The ideal type in Europe is, therefore, exactly what you would expect to see in any English Championship Show. However, there are very few breed specialist judges available, so most of the judging is by all-rounders, who again tend to 'spot' the showy, good moving dog, and often dogs of superior type are passed over in favour of lighter, less typical specimens.

The Europeans also have what are, in effect, 'notes for judges' which lay down certain details which are considered criteria essential to the breed. One of these refer to the 'Bite', where judges are told to penalise an undershot jaw, and , as is usual with the Europeans, all teeth should be present in the jaw, to the extent that if teeth are missing the animal can be barred from breeding, and cannot become a Champion.

Some countries, such as France, have a system of 'Confirmation' in order for dogs to be passed fit for breeding. A dog or bitch must either be placed 'Very Good' or higher, or be examined by a breed expert in order to qualify. The persons authorised to carry out confirmations are registered by the French Kennel Club (SCC) and are either breed specialists who have to undergo a course of training, or the All-Rounders licensed for the particular breed. While this does have pitfalls, at least most of the Mastiffs used for breeding are of reasonable quality.

Australia and New Zealand have very few Mastiffs. Both countries currently use the English Standard without change, although some changes are being discussed. The American Breed Standard follows the British Standard closely, with a few notable exceptions.

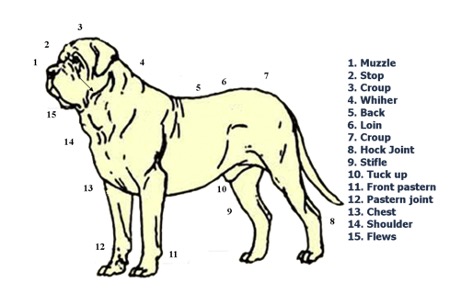

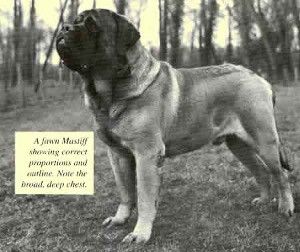

The British Breed Standard does not give specific guidelines to size and weight; it simply requests a "large, massive, powerful, symmetrical, well-knit frame." We are therefore looking for a very large, very powerful, and very massive dog, but the massiveness and height must come from the depth of the body rather than the legs, in the approximate proportions of two-thirds body to one-third legs. A Mastiff should not be too tall and gangly. The American Breed Standard asks for dogs to have a minimum height of 30 inches at the shoulder, and bitches should be 27.5 inches.

TEMPERAMENT

The Mastiff has a very loyal temperament; this is simply described in the British Standard as "Calm, affectionate to owners, but capable of guarding." There is a little more detail in the American Standard, and the words such as 'dignity' and 'courage' build up a good picture.

Several countries are introducing 'Temperament Tests' as part of the qualification towards gaining the title of Champion, and this is normally included in the Club Championship Show. This can lead to problems if a dog is rewarded for showing aggression, as can be the case. While it may be right to penalise a dog which is a quivering heap in the ring, no matter how good it may otherwise be, we do not want to go to the opposite extreme and encourage a dog to attack as proof of its 'guarding' abilities. The American Standard specifically states that "Judges should not condone shyness or viciousness."

HEAD

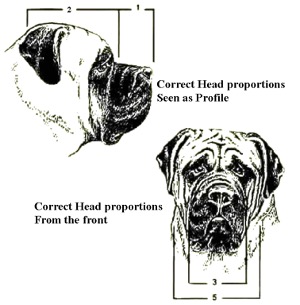

The Mastiff is an extremely 'head conscious' breed, and the description of the head forms the largest part of both the British and the American Standard. It is, however, quite difficult to visualise if one is not familiar with the breed.

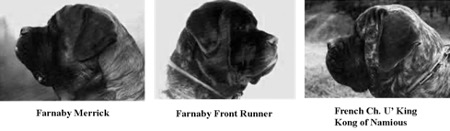

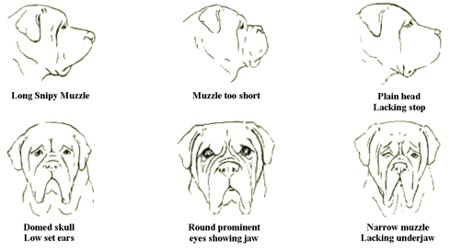

It is the head which really makes the mastiff; it must be big, broad and flat across the skull, with the ears set on at the highest point so that the line across the ears and the skull is continuous. The stop between the eyes must be pronounced, not shallow, and the muzzle itself must be very broad and very deep - these two proportions should be almost the same. So many Mastiffs have muzzles which narrow and appear to taper, or which are not filled out under the eyes, giving a weak appearance. It should, as the British Standard says, be blunt, cut of squarely. The length of the muzzle to the whole head should be as 1 to 3.

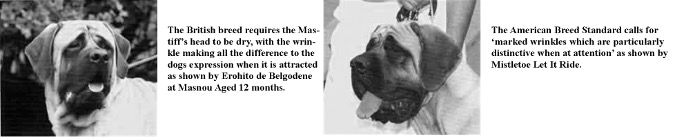

One very important point here is the question of wrinkle, and this differs between the British and the American Standards. The British Standard asks for the forehead to be flat but wrinkled when alert, whereas the American Standard calls for "marked wrinkles which are particularly distinctive when at attention". This one small phrase does make quite a difference to the appearance of heads. As far as the British Standard is concerned, this should mean that the head should be comparatively 'dry', with the wrinkle making all the difference to the dog's appearance and expression when the ears are raised and the dog is interested or excited. In British show rings this is being wrongly interpreted, and too many Mastiffs are showing a continually wrinkled head, combined with excessive folds of flesh down the sides of the cheek, making the Mastiff look rather like a Bloodhound. The difference between the correct amount of wrinkle and too much wrinkle can make all the difference to the overall picture.

To summerise, the two main faults that are seen in the show ring are narrow, weak muzzles and over-wrinkling. Of the two, the snipey, weak muzzle, lacking strength under the eyes, should be more severely penalised. However, the appearance of the head, in its finer points, has been interpreted in many different ways by many different people. All one can say in conclusion is that breeders, judges and exhibitors must be governed by the requirements of their national Breed Standard, which stipulates the correct and desired type of head. the Breed Standard is the blueprint and it should be followed in all its details.

EYES

Eyes should be small, set wide apart and dark in colour. There must not be red haw showing. The ears should be small and thin to the touch; again heavy ears are a common fault.

MOUTH

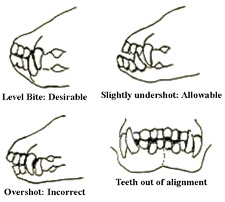

Again, we have a variation between the British and american Standards. The American Standard states that a "scissors bite is preferred" although a moderately undershot jaw should not be faulted. The British Standard states that the lower jaw may project beyond the upper, "but never so much as to show when the mouth is closed". This means that the Mastiff is, quite legally, allowed to be slightly undershot, but so many judges and even breeders do not appear to realise this. However, it should be obvious that the very short, blunt, broad muzzle - which is absolutely essential - is very difficult to combine with a scissor bite.

BODY

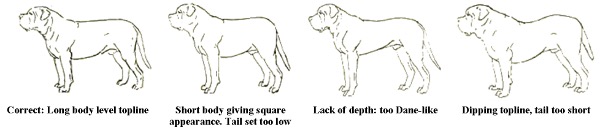

The body slightly longer than high, not square like a Bullmastiff. This is a very common fault, and some judges even praise the cobbiness of their winners, but this is certainly not a desirable attribute.

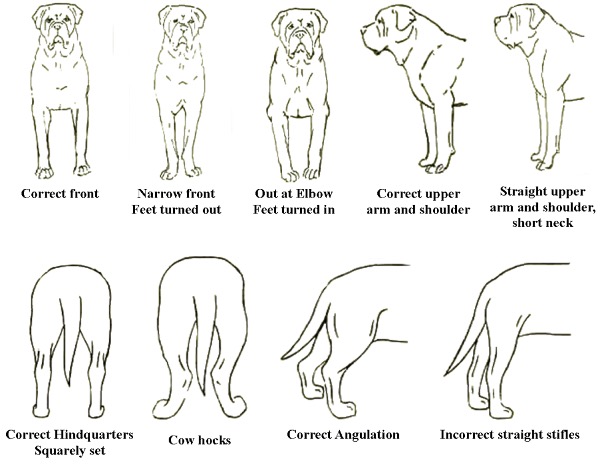

The chest must be broad and deep - as the saying goes, "you don't want two front legs coming out of the same hole." When viewed from the front, the chest must indeed be very broad and should come down at least level with the elbows. This will not be apparent in young dogs, but when a Mastiff is fully mature the chest must be well let down between the front legs so as to be level with the elbows. The topline must be flat, and very wide in a bitch. It should be arched in the dog.

FOREQUARTERS

The shoulders should be well-laid; they should not be upright - this is a bad fault. Upright shoulders may make for greater height, but the front action will suffer. Remember that the pasterns - the shock absorbers - will find it more difficult to absorb jarring from movement with upright shoulders, as the jolting leads straight down the shoulders into the front legs. In the Breed Standard the pasterns are required to be "upright", but even so, there should be a degree of flexibility. Correct pasterns and correctly placed shoulders give the essential cushioning to the heavy body when on the move.

HINDQUARTERS

The hindquarters must be strong, with a good bend of stifle. The American Standard asks for the joint to be moderately angulated, matching the front. The British Standard does not mention this angulation at all. It calls for hindquarters to be broad, wide and muscular, and the second thigh must be well developed. It seems obvious from this that angulation should be good, and not straight up-and-down like a Chow Chow. However, these straight and narrow hind legs are a common fault in the breed. Viewed from the side, the back end should resemble that of a shire horse rather than a racehorse.

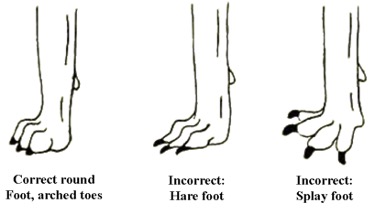

FEET

The feet should be round and cat-like; they should not be spread out or hare-like. These feet bear a tremendous amount of weight and must be up to the work entailed. The nails should be dark in colour and kept short. In show stock the dew claws are often removed when the puppy is a day or two old, but if these are not removed they must be watched to make sure they do not grow and curl round, sometimes back into the leg.

TAIL

The tail is set on high, and should be carried straight, but with a little curve upwards on the move or when excited. A low-set tail means that the hindquarters seem to slope away downwards, instead of being level and straight into the tail-set. The croup or rump must be strong and straight, and should not fall or slope away. Some years ago it was common to find a 'cranked' tail in one or two puppies in a litter - a throw back to the Bulldog - but these are now very rarely seen.

COAT AND COLOUR

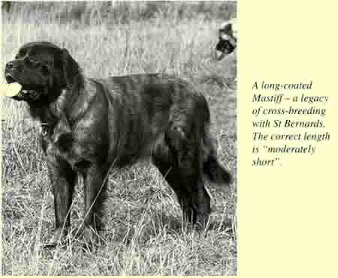

The coat should be short and close lying, but is allowed to be heavier and thicker over the shoulders, neck and back. There is a great deal or variation in coat lengths, from the really long-coated (due to the St Bernard ancestry, probably) to the Doberman type of coat. However, the 'moderately short' coat is correct.

Although officially there are only three colours in the breed - fawn, brindle and apricot - there can be quite an amount of variation in the fawn and brindle colours. The fawn can vary from very light, which used to be called silver-fawn, to much darker bordering almost on the red of the apricot, or a donkey-brown. Brindles also vary from being very nearly black in colour all over, with just a very few faint stripes, to an apricot brindle where the stripes are a very attractive apricot colour. However, a 'reverse brindle', where you have a light background (instead of a dark background) with a very few faint stripes of another colour is not desirable.

GAIT

The British Standard confines itself to "Powerful, easy extension", whereas the American description of movement is far more detailed. A Mastiff should move powerfully and freely, but it should not be expected to move like a racehorse, or a Great Dane. It should move not with grace, but with strength. The movement of a Mastiff can be likened to the earth-shattering movement of a Shire Horse. You cannot expect a dog of this build to move in any other way.

SUMMARY

It has to be admitted that other breeds have, of necessity, been used in saving the Mastiff, and so often these breeds have characteristics which are diametrically opposed to those required in the Mastiff. The St Bernard has a long coat and very often carries white markings; the Bullmastiff is square and has an ultra short muzzle; the Newfoundland has a shallow stop; the Bloodhound has far too much wrinkle; the Dogue de Bordeaux has liver pigment and yellow eyes. You only need just one dog of any breed to introduce something which is alien to the Mastiff, and future breeders have a very difficult job to breed it out over succeeding generations.